As a general-interest reporter, you have to cram knowledge and then discard it to make room for the next story, and you have to move on.

But at a book reading in Greenwich Village last night, I was bracingly reminded why some stories you do just matter more, and stick to your guts. Most of my tenure was spent covering pop culture, which certainly is important to a lot of people, but is rarely life-or death.

Not so this story.

|

| My first meeting & demonstration |

I just dug up a paper pocket calendar to find the date - November 6, 1989 - (right) that I first attended a weekly meeting of ACT UP - the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power - which had formed in March 1987.

I had been assigned to write a longform piece by Rolling Stone. I think one of my editors, Susan Murcko, had brought in a clipping about the group from the Village Voice. Or maybe the Times.

I wanted to suss out who was who and what was what, and the best way was to attend the open, democratic, freewheeling, sometimes fractious, often cruise-y Monday night forum at New York's Gay & Lesbian Community Center at 208 West 13th Street. It was run by "facilitators" and everything was decided by majority vote, after kicking off with the request that any undercover cops identify themselves (none ever did).

The facilitator, Ann Northrop - a lesbian former debutante and TV news producer - described ACT UP to those in attendance as "a diverse, nonpartisan group of individuals united in anger and committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis."

All true.

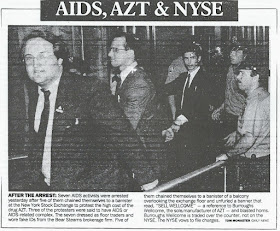

A few weeks earlier, in September, seven members of ACT UP had donned fake IDs and worn suits to infiltrate the New York Stock Exchange, chaining themselves to the VIP balcony and unveiling a banner saying "SELL WELLCOME," a reference to the pharma company Burroughs Wellcome which made the only approved AIDS drug at the time, and had priced it at $10,000 per patient per year. Meanwhile compariots outside staged a "die-in" blocking traffic. Many traders angrily screamed things like 'Die, faggots!' and 'Mace them!' |

| Wall Street, Sept. 1989 |

But a few days later, Wellcome lowered the price of its drug by more than a third.

This -- was impressive.

It turned out that the leader of that action, Peter Staley, knew what would be impactful because he had worked on Wall Street as a closeted gay man and had been participating in ACT UP secretly until his t-cell count got so low that he quit to become a full-time activist.

Staley was exactly my age - 28 - charismatic, impassioned, articulate - and in the fight of, and for, his life.

Just two days later, I attended my first demonstration, and my story was off and running.

A month later, I was with ACT UP inside St. Patrick's Day Cathedral for their choreographed "Stop The Church" interruption of mass led by Cardinal John J. O'Connor, who had opposed teaching of safe sex in schools and condom distribution. 4500 protesters showed up outside, and 111 were arrested.

The impact got muddied when, during communion, a renegade member threw a wafer angrily to the ground, which enabled critics - and President George H.W. Bush - to say they'd gone too far. But they of course got more publicity for it.

As I continued to report, I naturally found myself focusing on individuals -- most of them leaders, like co-founder playwright Larry Kramer, Staley, and Northrop, and Mark Harrington and Jim Eigo of the "Treatment and Data" committee, who were monitoring the status of medications and trials.

But I also found interesting Natasha Gray, a 25-year-old Bryn Mawr grad who hadn't known anyone with AIDS, who had gotten involved through the issue of housing for the homeless, many of whom were now becoming infected. Gray talked to me both about how empowering the group was in terms of self-education, but also about how she now was dreading losing her new friends to the illness. I decided to include her as a point of entry for readers like her.

|

| Fauci |

"They don't see the side of ACT UP that I do," Fauci said. "Intelligent, gifted, articulate people coming up with good, creative ideas."

My piece, "Act Up In Anger," ended up running in the March 8th, 1990 issue, at around 9000 words.

Some of the ACT UP subjects, while grateful, actually expressed concern to me that it would be too dauntingly long for the average reader.

When it hit the newsstand, my executive editor at Rolling Stone, Bob Wallace, ruefully warned me that, the way the magazine business and Rolling Stone were going, it would be less and less likely to give such space to such a story.

I ended up leaving the magazine a year or so later, to an editorship at Vogue -- where Anna Wintour surprised me by letting me write a series of social-issue stories with the famed photographer Mary Ellen Mark.

By 1996, the efforts and research of ACT UP had achieved the impossible: by pushing the FDA and Pharma companies, a combination treatment had been devised that kept HIV positive people alive.

And, in the pre-internet era, my ACT UP story faded from memory - both the public's and my own.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Cut to October, 2012. I went to see the documentary, "How To Survive a Plague," which chronicled the work of ACT UP, directed by member David France, who dedicated it to his partner who had died of AIDS in 1992. I went with my partner Syd, who it turned out, had been around in the early years of ACT UP as an ally, and we might have crossed paths without knowing it way back when.

The movie had been out for a month, but I hadn't been in any rush to see it. Maybe part of me thought I already was familiar with the story. But also, maybe part of me needed to be in the right mood to relive those harrowing days in NYC when we were losing people we knew and artists we admired by the dozens, hundreds, thousands. (One I perhaps knew best, B.W. Honeycutt, the art director of Spy magazine, died in January, 1994. He was 40.) By the time the film was released, I'd had several friends who had been living with HIV for years and years.

As soon as the movie began, I teared up. Their fierce determination, auto-didacticism and accomplishment remained singular.

But I didn't get really shattered until the end, when there was a contemporary round-up of survivors, and I saw so many familiar faces - Harrington, Eigo, Kramer, Staley - who had lived to tell the tale, and enabled so many others to.

They also expressed feelings of guilt: As Staley says, "Like any war, you wonder why you came home."

I dug up and re-read my piece. I felt terrible that I hadn't stayed in touch with any of the activist heroes, and hadn't tracked their fates. Part of it may have been the feeling of having been a hanger-on who was present for so much but not participatiing. Also just the journalism churn. And life.

But thanks to Facebook, I was able to connect with several. Eigo and I would soon run into each other in the audience of an off-off-Broadway play; happily he had gone back to playwriting, which all this activism had derailed. He came to the April 2019 reading of a play I had written, sat in the front row, and wrote the loveliest of reviews, revealing why insiders used to call him ACT UP's "St. Francis of Assisi."

(I also found out that Ron Goldberg, one of the activists who was bringing the documentary around to schools, was the same Ron Goldberg I had gone to summer camp with in Maine.)

But my biggest revelation in re-reading the piece was Natasha Gray. I had forgotten her name.

Which is kind of amazing, because she grew up to be a NYC private school history teacher -- and had taught both my daughters. She had never said anything to me about it either.

Turns out we both had been so in new personae we couldn't wrap our heads around our past lives. Additionally, all her ACT UP trove had been wiped out in a flood in a family house.

I tried lobbying my daughters' school to hold a screening of the movie. After all, they had been taught of civil rights activists, Ruby Bridges had even spoken at the school. Whereas the ACT UP actions had happened closer to their lifetimes, and had allowed their teachers to not just live, but be out without fear of reprisal. And it was all because the activists had proved the power and utility of education, teaching themselves about science and government.

I was basically ignored, and I decided to let it go, but it was disappointing. (*see post-script from Natasha in first comment below.)

On February 3, 2020, I sent Natasha some photos of a group reading I'd attended in Brooklyn of Staley, Goldberg, Sarah Schulman, and others, about their times with ACT UP, and she and I made plans to get together.

But another plague would quash that plan.

A few months later, in May, Larry Kramer died. I sent her Peter Staley's warts-and-all memorial tribute to Larry on Facebook. It reads in part:

Peter Staley and Larry Kramer, back in the day I just got off the phone with Tony Fauci. I broke the news to him via text earlier today. We’re both surprised how hard this is hitting. We both cried on the call.I’ve told Larry to fuck-off so many times over the last thirty years that I didn’t expect to break down sobbing when he died.....Larry’s timing couldn’t be worse. The community he loved can’t come together – as only we can – in a jam-packed room, to remember him. We can’t cry as one and hear our community’s most soaring words, with arms draped on shoulders in loving support. Broadway has no lights to dim, which it surely would have.

Gray thanked me for sending it, adding: "I want to go to a funeral like a human being."

* * * * * * * * * * * *

As I write this, Covid has already killed more Americans than AIDS and is still going, despite having had a vaccine for the past eight months. (Imagine if AIDS had garnered such a quickened medical effort at the time.)

|

| James Krellenstein, Gonsalves and Staley outside Klain's house |

In late September, activists set up a 12-foot high pile of fake bones outside the Maryland home of White House chief of staff Ron Klain, as a protest against America's inaction in distributing the Covid vaccine globally to help prevent the disease's spread.

The activists included Peter Staley and Gregg Gonsalves of ACT UP. A similar protest was staged outside the home of the Moderna CEO. It may not have achieved the headlines ACT UP used to, but it still garnered attention. And Staley said he was meeting - again - with Fauci.

During the pandemic I have rarely attended indoor events, but on October 12, I decided to be on hand to witness Staley reading from his new memoir, Never Silent, which recounts not just his activism but his later battles with a crystal meth addiction.

He had purposely arranged for it to be held in the same West 13th street Gay Center ground floor space where those ACT UP Meetings had been. The murals that decorated the walls have been preserved in pieces as part of a multi-million dollar renovation.

The vibe in the room was a mixture of nostalgia, passion, sadness, and pride. Silence=Death and ACT UP t-shirts and buttons were for sale.

ACT UP veterans Maria Maggenti and Karl Soehnlein welcomed the socially-distanced, mostly masked attendees by invoking the old facilitator introduction.

Then my camp buddy Ron Goldberg introduced Staley with his signature sass: "What can I say about Peter Staley that's not already been said--by Peter Staley?" He said Peter originally wanted to call it "Me Me Me," or just "My Fucking Memoir."

He eventually wound his way to his true feelings. "It's still a pretty good read. Some of it sounds like a really good heist movie. If you ever wondered how Peter and his power tools invaded Burroughs Welcome or the Stock Exchange, or put that condom over Jesse Helms' house? It's there in fabulous detail." He commended Staley's bravery, they hugged, and then Staley took the podium.

Before he read, came a prelude with some eerie symmetry: he asked people to reach out to two members of their community who are dying -- one of ALS and one of cancer who just checked himself into hospice.

And then he read from the chapter "Searching for ACT UP."

Not having yet read the book, I didn't keep filming to the end of the chapter, and was gutted when he said that after he got home to watch the coverage on the local news, a chyron identified him as "PETER STALEY: AIDS VICTIM."

I bought a copy of the book for my 24-year-old, who had graduated from Staley's alma mater, Oberlin, during the first months of this pandemic.

He wrote her a double-edged piece of advice that I hope she takes to heart:

POST SCRIPT: during our re-connect, Natasha Gray wrote me an interesting email about an unreported aspect of ACT UP. I wanted to get her permission to include in the post, and didn't hear back from her till after it had been posted. Couldn't figure out how to shoehorn it, so adding it here as a footnote.

ReplyDelete"You would think as a historian with a personal connection I would be all over this but it feels a bit too close or maybe now too far away to comfortably engage with.

"Why is money being written out of the history? There seems to be a narrative that this was a heroic "grassroots" effort fueled by self-sacrifice and general virtue. My memory is that ACT UP was swimming in cash. Part of the reason it could function as a diverse, grassroots organization was that there was ZERO infighting over funding. Everyone's crazy idea got funded. Everyone could go on a road trip protest. The organization even decided not to take a member who had stolen $30,000 dollars to court. There seems to be a discomfort with talking about money. Perhaps it is related to the "rich white gay men only cared about themselves" accusation against ACT UP. Perhaps it is left wing historians being dainty about cash. Seriously, for activists of the future, understanding fundraising and how to run a mixed class organization is important. I hate to think of young activists judging themselves unfairly for not being able to build a big organization out of virtue.

And then today she added the explanation:

"People often associate progressive politics with anti-capitalism but private property makes protest possible. Think of Harvey Milk having his own camera shop. Think of Selma bus boycotters having enough privately owned cars to take people to work. Organizations need to rent rooms to meet in. Buckets of wheat paste don't appear on their own. It took a lot of money to transform the image of gay men with HIV from 'diseased sex-perverts' into noble champions of social justice."

Great comment, Natasha. I have a chapter in my book describing all the ways we raised money. The first year of ACT UP was very hand-to-mouth -- we rarely had more than $10K in our bank account. But after our direct mail campaigns took off (and then the art auctions), things really took off. Before the auctions, I worked with the fundraising committee to create three sources of funding (three-legged-stool approach): merchandise sales, benefits (mostly at dance clubs), and a national direct mail campaign (this became the biggest leg). But they were all based on thousands of small donations/purchases/etc. Up until the auctions, we were the Bernie Sanders of movement fundraising. ;)

ReplyDelete